.jpg) Red-shirted protesters in Bangkok on Friday. Farmers who say they were never interested in politics are donating large sums to the red-shirt movement. (Agnes Dherbeys for The New York Times)

Red-shirted protesters in Bangkok on Friday. Farmers who say they were never interested in politics are donating large sums to the red-shirt movement. (Agnes Dherbeys for The New York Times).jpg) The widow of Praison Tiplom, a protester killed in Bangkok, held a picture of her husband during his funeral last Saturday. (Thomas Fuller/The International Herald Tribune)

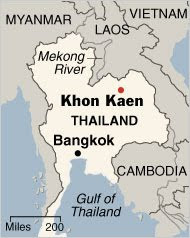

The widow of Praison Tiplom, a protester killed in Bangkok, held a picture of her husband during his funeral last Saturday. (Thomas Fuller/The International Herald Tribune).jpg) The red shirts have a core of support in Khon Kaen. (The New York Times)

The red shirts have a core of support in Khon Kaen. (The New York Times)April 23, 2010

By THOMAS FULLER

The New York Times

KHON KAEN, Thailand — Six weeks of demonstrations by red-shirted protesters turned violent this week in Bangkok, but the capital is not the only place with a whiff of insurrection in the air.

On this poor and rugged plateau in Thailand’s hinterland, farmers who say they were never interested in politics are donating hundreds of thousands of dollars to the red shirt movement. In at least three northeastern cities, red shirts are holding nightly rallies, sometimes drawing thousands of people.

This week, Red Station Radio, an antigovernment FM station based here in Khon Kaen, about 280 miles north of Bangkok, broadcast a warning that a train was heading to Bangkok carrying military vehicles. In no time, hundreds of red shirt supporters, who have followed the protests daily with the broadcasts, mobilized to block it.

Indeed, this rural region — home to a third of Thailand’s population — forms much of the core of the red shirt movement, demonstrating the magnitude of the challenge facing Prime Minister Abhisit Vejjajiva, whom the protesters are pressuring to step down and call new elections.

On Friday, protest leaders in Bangkok offered to negotiate an end to the standoff if Mr. Abhisit would dissolve Parliament within one month, instead of immediately. The gesture eased tensions slightly a day after one person was killed and scores were wounded when grenades exploded near red shirt barricades in the capital.

But the anger here in the countryside will not be easily dissipated after simmering for more than three years since the military coup that overthrew Thaksin Shinawatra, the billionaire tycoon turned prime minister, who is seen as the first politician to have seriously addressed the concerns of the poor.

Mr. Thaksin’s wealth and patronage network remain important drivers of the protests, but the movement also appears to be taking on a grass-roots character, with farmers and villagers finding common cause and demonstrating a new assertiveness.

The people of this northeastern plateau, known as Isaan, speak dialects similar to the Lao and Cambodian languages and generally work as farmers, manual laborers and factory workers.

The red shirts have railed against the “double standards” in Thai society — the wealthy, the Bangkok elite and the top military brass break laws with impunity, the protest leaders say, while the poor are held to account.

Radio stations like Red Station Radio have played a crucial role in spreading that message in the countryside. Red Station Radio, which operates from an unmarked office, has rapidly expanded since it started operating in November, and now has six affiliates in and around this city.

Its disc jockeys urge supporters to disrupt visits by senior government officials. One D.J. is even a full-time police officer, who uses the on-air name Noi Tamrung to protect his identity and, he says, avoid being fired. Many other police officers also back the movement, its supporters say.

“Don’t come here — that’s the message,” said Noi Tamrung. “We reject anyone from this government.”

Government supporters have called for the stations to be shut down, and the government has already banned some Web sites of the red-shirt movement, including the site of Red Station Radio. But the red shirts here have vowed to physically block any attempt to close the station, such is its support among farmers.

One farmer, Takum Srihangkod, listens constantly to broadcasts of protests in Bangkok with a cheap Chinese-made radio that he tucks into his waistband, next to his slingshot.

“Abhisit doesn’t want anything to do with poor people,” Mr. Takum said of the prime minister as he tended his cattle. His radio even stayed tuned to the protests as he muscled out a newborn calf in a difficult birth.

Supporters of the government often portray the red shirts as a mob for hire, mercenary protesters who receive a daily stipend. In a country with a long tradition of vote buying, that may be true for some.

But villagers bristle when asked if they are being paid to protest. Local officials and police officers describe a widespread fund-raising effort to support the demonstrators in Bangkok.

“We help each other,” said Triem Tongkod, a farmer who grows sticky rice in a village outside Khon Kaen. Pickup trucks with loudspeakers travel through his village periodically asking for donations. “You give what you can afford,” Mr. Triem said.

Last Saturday, at a Buddhist temple about 35 miles outside Khon Kaen, Mr. Triem was one of thousands of people who attended the funeral of Praison Tiplom, a protester killed in the April 10 crackdown on the red shirt protests in Bangkok. A total of 25 people died, including five soldiers, in circumstances that remain under investigation.

The deaths of protesters have become an opportunity to rally support and gather donations. At the funeral last Saturday, organizers collected about $9,400 for Mr. Praison’s widow, according to Num Chaiya, a D.J. at Red Station Radio who helped organize the funeral.

It was far from a typical somber ceremony, the crowd cheering loudly as Mr. Praison’s coffin, draped with the Thai flag, was carried around the crematorium three times. “Give a big hand to a warrior of the people!” Mr. Num exhorted the crowd. Almost all wore red.

Organizers of the red shirts have begun selling DVDs eulogizing the dead protesters and showing scenes of the April 10 crackdown. Along the highway, one DVD salesman, Pornchai Nanthaphothi, operates a stall festooned with red flags and other red shirt paraphernalia. A bandanna he sells is embossed with the words, “I’m not scared of you.”

“This area is nearly 100 percent red,” Mr. Pornchai said.

Successive Thai governments, including the current one, have tried to develop the Isaan region, but persistent income inequality and the need for more doctors, universities and jobs have fueled the protest movement, said Krasae Chanawongse, a medical doctor by training who has worked as a minister in four previous governments.

Thailand’s centralized political system has engendered a “colonial attitude of governors” posted here, he said. “They are more or less dictating, not consulting,” he said.

Some analysts question the durability of the red shirts, because of their close affiliation with Mr. Thaksin, but supporters here in the northeast say the movement has taken on larger goals.

In a country that has seen more than a dozen coups over the past eight decades, Chaisawat Weangwong, a 42-year old rice farmer, said the crisis had opened his eyes to the influence of the military in Thai politics and the need for a system where “the majority chooses the winner.”

“This is not for Thaksin,” he said. “This is for democracy.”